...

I found it quite fascinating that his memoir was, in its own way, a book-length erasure poem, composed alongside his wife. It’s quite romantic.

...

Posthumous reflections on Breyten

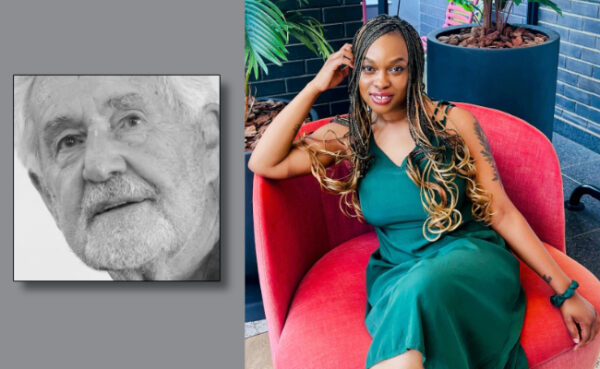

Contemporary poets in South Africa frequently engage with the lyricism and literary legacy of Breyten Breytenbach (1939-2024) in their own work. The oeuvre Breytenbach leaves behind is as vast as it is impressive. Academics, journalists and writers have repeatedly described the bard as an iconic figure – a poet who, over several decades, expanded and transgressed the boundaries of the Afrikaans language and brought renewed attention to African poetry. Besides his unique literary idiom, peppered with neologisms (“Breytenbachisms”) and idiosyncratic imagery, there is the poet’s intellectual legacy to take into account. His public career is defined by lyrical and essayistic work which, in the 60 years since his debut as a Sestiger, has inspired, challenged and brought surprising insights to many readers. Even younger fellow poets have felt drawn to him, while others have had to commit a “Bloomian patricide” to develop their own voice. In one way or another, poets have been touched by the work and aura of the master, even though they may not be part of the same literary tradition.

On 27 September 2025, the first Breyten Breytenbach Poetry Prize was awarded in Cape Town to Danie Marais’s collection, Ek en jy bestaan nie. The goal of the Breytenbach Prize, according to a press release from Media24-Rapport-kykNET, is to promote Afrikaans by annually recognising an original poetry collection written in Afrikaans. As stated by the organising body, the winning author is not required to adhere to Breytenbach’s poetic line, or to embrace an aesthetic that connects them to Breytenbach.

Breytenbach’s poetry has influenced numerous writers in Afrikaans. Literary influence, as a concept, is diffuse and refers to a degree of indebtedness or inspiration that cannot be quantified or measured with empirical precision. Writers refer to Breytenbach’s lyricism in paratexts, or they reference it in intertexts or interviews (epitexts). In conversation, some claim to be indebted to him, while others deliberately conceal any Breytenbachian frame of reference or system of allusion. Of course, there can also be simple respect and admiration without a strict, identifiable influence or aesthetic affinity. In the wake of Breytenbach’s death in 2024, a series of obituaries have expressed numerous authors’ appreciation of and admiration for this poet who left a deep mark on the African literary landscape.

The present series of conversations builds on the spirit of recognition and appreciation initiated in tributes published after Breytenbach’s death. In the dialogues, a total of 30 African poets reflect on their own experiences of Breytenbach’s poetry. The aim of the dialogues is to shed light on Breytenbach’s “legacy” as a poet, from the perspective of a polyphonic group of South African poets. I pose five questions to each interlocutor, which they answer concisely. The questions explore the extent to which they have read and imagined Breytenbach’s lyricism, how they would describe their own private reading of his poems, and their familiarity with his oeuvre and the various phases of his writing career. Each poet constructs their own Breytenbach. The diversity of poetic personas and the different resonances of Breytenbach’s work in the poetry of others are highlighted through a prism-like lens in these conversations.

The publication of the series started on 3 December 2025, one year after the poet’s funeral at the famous Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. The Nachleben of Breytenbach’s poetry plays out in the creative and contemplative project of a younger generation of poets. This project was partly inspired by Louise Viljoen’s chapter, “Afrikaanse digters in gesprek met Breytenbach se digterskap”, included in Die mond vol vuur: Beskouings oor die werk van Breyten Breytenbach (2014; pages 243-70). More than a decade has passed since the publication of Viljoen’s piece, and while Breytenbach’s oeuvre is now complete, its impact is by no means over. The contributions collected here, which have been initially published on the online platform Voertaal, will reach a broader audience than Viljoen’s important inventory, “where Afrikaans poets recognise Breyten Breytenbach as an important conversational partner … by addressing him by name or referencing his work”.

YT: Nkateko, Breytenbach compiled his widely published collections in three substantial volumes: Ysterkoei-blues: Versamelde gedigte 1964-1975, Die ongedanste dans: Gevangenisgedigte 1975-1983 and Die singende hand: Versamelde gedigte 1984-2014. In Breytenbach’s lyrical work, is there a specific collection or even an aesthetic phase that stands out to you, one that you prefer for a particular reason? Which Breytenbach has been meaningful to your poetic career? Do you prefer his early work or the “late style” in his lyricism? Would you say there’s any literary influence, such as a moment or even a specific poem, that has guided your own poetic voice in any way?

NM: Hi, Yves. Your question takes me back to my raw and radical secondary school days, where I was introduced to the Anti-Apartheid Movement and the poetry and prose of those who fought against racial segregation in South Africa and beyond, and where I learned how the dehumanisation of the toppled regime crossed every line imaginable. Not only was I reading about the inhumane legislations of the regime in history class, but I was seeing their implications brought to life in my English class, in poems such as Mongane Wally Serote’s “City Johannesburg” and books such as Breyten Breytenbach’s The true confessions of an albino terrorist. It was a mindshift, a revelation, for me as a young black woman born in a township, that the violent struggle my parents and grandparents are still healing from was neither black and white nor blacks versus whites. It was and is a war of ideologies.

My poetic voice is contextualised in the aftermath of this infamously traumatic period, so every artist engaged in the conversation – whether through poetry, prose, photography or performance – had a proverbial seat at my mind’s table as I built my own poetic and literary identity and lineage. I am eternally grateful to my secondary school English teachers, who noticed and nurtured my love for reading and specifically for poetry, because I would not have read as widely as I did, had they not encouraged me. However, I have to admit that Breyten Breytenbach dined at my nonfiction/memoir/life-writing table, through The true confessions. His poetry was a much later discovery for me, and even then mostly through translations. My entry point there was the prison poems: Die ongedanste dans: Gevangenisgedigte 1976-1983. By the time I began studying those poems intently, I was in medical school and was curious about the mental and physical implications of imprisonment.

YT: In addition to the explicitly socio-critical poetry, there are the poems that portray the imagination of Africa, the many love poems, the lyricism in which decay, rotting and death are central motifs, the nomadic Middle World discourse and the Zen Buddhist poems. Is there an aspect of Breytenbach’s poetry that you have read with particular interest or affinity?

NM: Oh, it has to be the love poems! Breytenbach’s “Soos van vlerke” is one of my favourite love poems of all time, and it was a great source of comfort to me when I was in a long-distance relationship years ago. I was initially drawn to the poem by the back story: He was in a maximum security prison, serving time for high treason against the apartheid government, and he wrote the poem to his wife while she was waiting for him to come home to her. My favourite lines are the final four, where he writes:

My liefde moet soos ’n engel by jou bly

soos vlerke, wit soos ’n engel.

Jy moet van my liefde bly weet

soos van vlerke waarmee jy nie kan vlieg nie.

YT: Breytenbach also expressed himself through contemplative and lyrical texts. He gave public speeches, and he wrote Notes from the Middle World, the trilogy ’n Seisoen in die paradys, The true confessions of an albino terrorist and Return to paradise. The literary genres in which the writer spoke and created a rich, symbolic universe are closely interconnected. This can also be said of his painting and drawing work. Which texts have inspired you, and which reading experiences connect you to specific texts in his body of work?

NM: The true confessions of an albino terrorist was my introduction to Breytenbach’s work, so I would say that this is one of the books that made me fall in love with the prison memoir as an art form. It sits alongside Nelson Mandela’s A long walk to freedom on my shelf.

Years after my first encounter with The true confessions, I was learning about erasure and blackout as a poetic device, and I came across a journal paper that led me back to the book. In the article “‘In an attempt to erase’: Breyten Breytenbach’s prison writing and the need to re-cover”, Guillaume Cingal quotes from Breytenbach’s reflections on the process of writing his prison memoirs:

My wife typed the tapes. I used her transcripts as “rough copy”. These I would blacken, add to, delete from, change about, and she would retype a clean version for me to go over again if needed.

I found it quite fascinating that his memoir was, in its own way, a book-length erasure poem, composed alongside his wife. It’s quite romantic.

YT: How did you first encounter Breytenbach’s work? What impression did you have of that first meeting, and has it changed throughout your reading journey? What role do you attribute to Breytenbach in relation to Afrikaans and South African poetry? He referred to Afrikaans as a “mixed language” – a Creole language – and especially as a language of Africa.

NM: I have my secondary school history and English teachers to thank for all of the literary introductions that have changed my life. Breytenbach’s “Soos van vlerke” and Antjie Krog’s “Ma” are strong contenders for my favourite Afrikaans poems: When one is learning a language, clarity and simplicity are priceless gifts. These poems first made me feel as if I understood what I was reading, and later, through various experiences in my life, that someone understood what I was feeling.

YT: Could you express in a few sentences the groundbreaking or even iconic significance of the poet Breytenbach? Or, in other words: How would you recommend his poetry to future readers, both in South Africa and elsewhere?

NM: I am a romantic, so my go-to recommendation would be the love poems that Breytenbach wrote to his wife. His 2002 collection Lady one: Of love and other poems is a gem.